Millions of dollars subsidize West Virginia dog racing each year

West Virginia is the last refuge for commercial dog racing in the United States. Greyhound racing would have ended years ago, but live racing is subsidized with $17 million in annual subsidies.1 State lawmakers voted in 2017 to end this annual giveaway, but the measure was vetoed by Governor Jim Justice.2 As a result, the state continues to lose millions of dollar each year propping up a dying industry. These funds could be better invested improving the state's crumbling infrastructure, or helping public service employees such as teachers and firefighters.

Most West Virginia voters oppose the continuation of greyhound racing subsidies. According to a November 2019 survey by Mark Blankesnship Enterprises, 81% of West Virginia voters oppose greyhound racing subsidies while only 14% support the subsidies.3

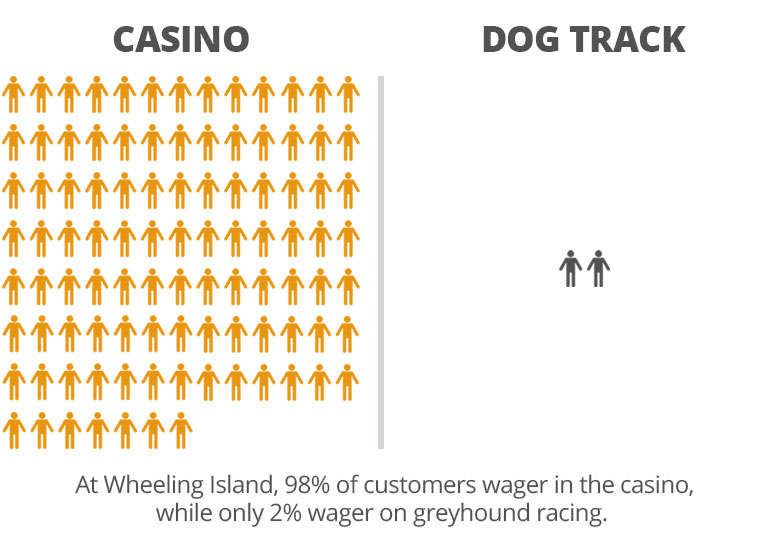

Attendance at WV dog tracks

West Virginia tracks have not recorded attendance since 2000, but in a report commissioned by the state of West Virginia and published in 2015, Spectrum Gaming Group estimated that attendance at Wheeling Island declined 99% between 1983 and 2013.4 Spectrum estimated in 2015 that attendance was less than 13,000/year, or an average of 50 patrons per day.5 Low attendance persists despite the fact that Wheeling Island’s seating capacity is 2,400.6

Data provided by Wheeling Island management showed that 2% of customers predominantly wager on racing, compared to 98% of customers who predominantly wager in the casino.7

Dramatic incease in purses

Purses have increased dramatically since 1990. At Mardi Gras, the prizes awarded to winning dogs increased 281% — from $1.6 million in 1990 to $6.1 million in 2013.8 Such purses have been artificially inflated by subsidies from racetrack casino Video Lottery and table games. Video Lottery accounts for 95% of the casinos’ greyhound racing subsidies.9 In the state of West Virginia, purses were higher than the entire live greyhound racing handle: $17.2 million vs. $15.8 million.10

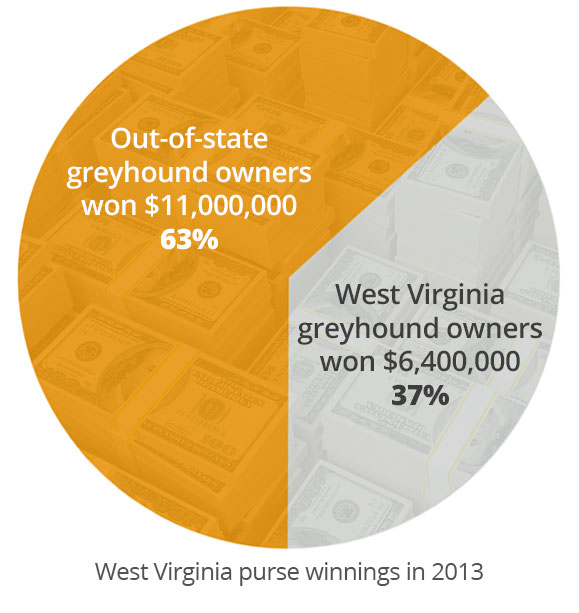

The majority of purses go to out-of-state residents

In West Virginia, 63% of purses, $11 million out of $17.4 million in 2013, were won by greyhound owners who live out-of-state.11

At Wheeling Island in 2013, only $2.6 million out of the $11.7 million in purses (22%) was paid to West Virginians. Residents from the state of Kansas alone won more money than West Virginia residents: $3 million vs. 2.6 million.12 Out of 260 entities that won purse money at Wheeling, just 30 (12%) live in West Virginia.13

Small minority wins vast majority of purses

Out of the 368 entities that raced greyhounds in West Virginia in 2013, the top 10 (less than 3% of all entities) collected 42% of the purses.14 The top 20 (5.4% of entities) collected more than half of all purses.15 The top 50 (13.6% of entities) collected 84% of purses. This means that the bottom 86.4% of entities, over 300 of the 368 in total, collected just 16% of the total purses.

The top two entities alone, both out-of-state, collected $1.8 million, or 15% of the purses.16 Thus, two out-of-state entities collect nearly the same amount as the bottom 318, or 86.4%, of entities. Spectrum drew particular attention to the impact of deeply unequal purse distributions:

“We find these numbers to be important because they demonstrate that the purse awards are limited to a select number of greyhound industry participants, which, in turn, limits the statewide impact, especially when so many of the awards indicate the vast majority of participants do not earn enough to support themselves through greyhound racing.” 17

Small minority wins vast majority of the development fund

In addition to subsidies for regular purses ($16.8 million in 2013), West Virginia taxpayers subsidize the Development Fund ($5.5 million in 2013). These awards go to West Virginia breeders, but like regular purses are highly concentrated.18

In 2013, 63 participants, a 10-year low, competed for the $5.5 million subsidy.

The top 10 entities collected 49% (over $2 million) of the awards and the top 20 entities collected 70% of the awards.19

The top two entities alone collected 19% of the Development Fund purses in 2013. Following this statistic in the report, Spectrum wrote, “As we have shown throughout this report, a handful of entities collect the vast majority of purse awards, whether for regular purses or for bonus awards for state-bred dogs.”20

Spectrum ultimately concluded, “With so few entities dominating the awards, the economic impact of the distributions is limited, as the vast majority of greyhound owners would not be in an economic position to hire employees.”21

Greyhound racing could not exist without subsidies

Casinos are subsidizing greyhound racing

Purses paid to West Virginia greyhound owners would be less than $1 million if the casino subsidies ended. In 2013, they were $17.7 million.22

Spectrum finds, “Without the purse subsidies from the racetrack’s gaming operations, purses would decline to such a level as to make it uneconomic for kennel owners to continue to race greyhounds in West Virginia.” This understanding, according to the report, is unanimous among greyhound racing participants and observers alike.23

Positive economic impact to ending greyhound racing

In 2015, Spectrum concluded that ending greyhound racing would have a “negligible impact on the state’s unemployment rate” and “many of the displaced greyhound employees could be retained by the tracks in new positions.”24

Millions of dollars subsidizing the greyhound industry could also be spent on schools and healthcare. 25

They further pointed out that people who previously avoided the state on moral grounds would now view West Virginia as a tourist destination.26

Revenue generated from greyhound racing for towns, counties, and the State of West Virginia in decline

Counties and towns where tracks are located receive distributions based on live handle. With live wagering on greyhound racing in decline, so too are these distributions.

In Wheeling and Cross Lanes, distributions declined 46% from 2008 to 2014, from $84,705 to $46,028. The amount generated for Ohio and Kanawha counties declined 54% during the same period, from $33,625 to $19,530.27

Between 2000 and 2014, revenue generated for the state of West Virginia from greyhound racing declined by 64%, from $3.3 million to $1.2 million.28 In 2017, revenue generated for the state of West Virginia from greyhound racing fell below $1 million.29

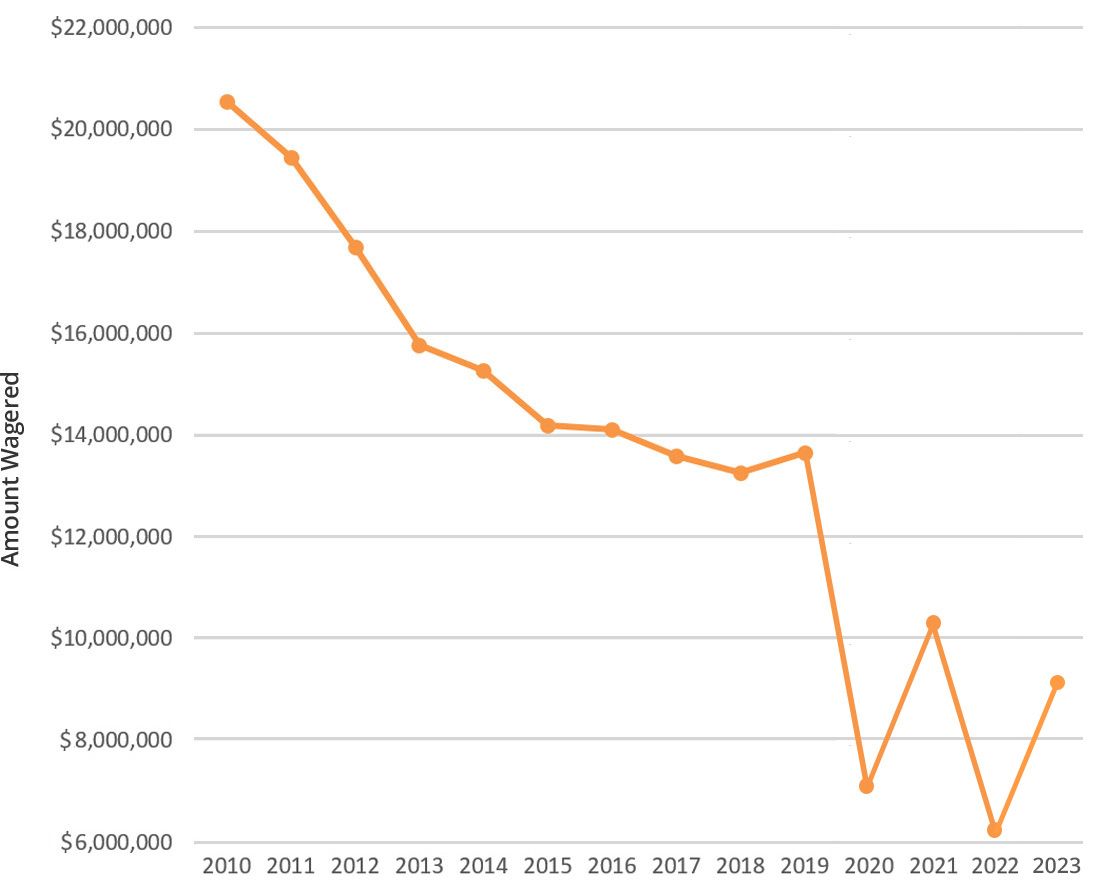

Decline in Wagering

Gambling on live dog racing in West Virginia declined by 57% between 2010 and 2023, following a decades-long national trend.30 The amount wagered has dropped from $20,554,006 in 2010 to $8,819,511 in 2023.31

Wagering decline in West Virginia. 2010: $20,554,006; 2011: $19,460,613; 2012: $17,697,117; 2013: $15,771,127; 2014: $15,261,865; 2015: $14,186,746; 2016: $14,100,164; 2017: $13,581,206; 2018: $13,263,216; 2019: $13,645,945; 2020: $7,310,477; 2021: $10,407,032; 2022: $6,269,449; 2023 $8,819,511.32

Learn more about dog racing in West Virginia:

Stay up to date and learn how you can help.